One of the key missions of product management is understanding the customer. Who, exactly, is going to buy your product? Why?

Yes, product management does other things, as well, and determining other things like how much the customer will pay is another important thing to understand. However, to me, everything revolves around “who is going to buy your product and why?” Fail at answering that correctly, and things go south in a hurry.

So: who is still buying cameras, and why?

Certainly professional photographers still buy cameras. Maybe not as often as before, but the camera is their primary tool and a pro shooter generally is interested in keeping their tool current. Specifically, professionals want the following two things in any new camera (the why): makes the job easier or gives them better results. Both are important to staying competitive and keeping clients happy.

So, how did Canon and Nikon do on that this round? It’s difficult to tell from marketing materials.

Both the Canon 1DX Mark III and the Nikon D6 changes from earlier models seem to revolve mostly around focus performance, and that’s very difficult to put into words. It’s difficult for us reviewers to categorize or summarize, too. Neither company is doing a good job of saying “you need to buy this new camera because…”.

I suspect some of that is the small size of the market coupled with the long product cycles. Both companies seem to assume that pros just regularly upgrade, either every cycle or every other cycle, and they don’t have to put too much energy into marketing their product. In essence, they’re ignoring Sony and the A9 Mark II in doing so, which is a mistake. Moreover, whatever mirrorless solution Canon and Nikon come up with to replace/supplement their top pro DSLR is going to have to answer that question, and in so doing, it’s going to hit their DSLR sales when they do so.

What I want: No change in form or controls that isn’t a clear improvement, less viewfinder blackout time, better integration into workflow, and more performance and control of autofocus. Image quality (or size) improvements are welcome, but not particularly needed.

Next up, we have the prosumers. Yes, they’re still buying cameras, although again not as often as before. Prosumers are a tougher sell than pro shooters, believe it or not. They’re fickle as can be, partly because they chase features and “magic”. A true prosumer camera design is a bit like throwing in everything but the kitchen sink. Curiously, the prosumer group tends to know more about camera specs and technical information than the pros.

Look at all the commentary on the Internet. In the prosumer group it’s not uncommon for them to say “but Camera X doesn’t have Feature Y, while Camera Z does.” Focus shift shooting, pixel shift shooting, on-sensor stabilization, 4K/60P, the list goes on forever, it seems. Moreover, many of the features being chased are either somewhat irrelevant or not particularly meaningful to most of their actual shooting. Even a half stop dynamic range difference is not going to make a difference most of the time, and BSI versus FSI sensor tech in and of itself doesn’t do much for fill factor on large sensors.

The prosumer group is highly vocal, highly critical, and not averse to shifting their loyalty. But they’re buying on lots of small things that often don’t show up in their shooting. They’ll read the specifications and debate them endlessly, and they’ll start by defending the brand of their choice right up to the point where some feature triggers them into grass-is-always-greener-on-the-other-side syndrome.

Moreover, prosumers love “magic.” Eye detect autofocus is one of those magic bits. While I’m not finding any eye detect autofocus system consistently focusing on the pupils where I’d want it to, apparently this group is happy with the current implementations because it gets focus “more right” than they’re used to with their older cameras. That’s because the typical prosumer is not very pro but is very 'sumer.

This is an area where Canon and Nikon aren’t doing so well with their DSLRs (the D780 being an exception). Canon seems to be about to transition their prosumer base from DSLR (5D Mark Whatever) to mirrorless (R5). That’s likely to set off some who want to stay in the DSLR realm, though. Put more kitchen sink features into the R5 than are in the 5D and the prosumer I’m describing is then given three choices: (1) suffer with what they’ve got; (2) switch to the R5; or (3) switch to another system.

It’s #3 that a camera company can’t afford: brand loyalty in prosumers means significant lens and accessory sales long term. That’s why Nikon’s update to the D780 makes a lot of sense, particularly so if they also make a D880 and a Z8 in the near term. Nikon would be saying to their full frame prosumer base that they’ll sell them a DSLR or a mirrorless system.

But prosumer DX and APS-C is a different story at both Canon and Nikon. I’d say that the 7D and D500 user probably feels pretty abandoned: no camera updates in forever, no new appropriate lenses, no clear mirrorless transition. I can’t speak for Canon, but I know that Nikon’s thinking is “transition this user to full frame.” I’d call that wrong thinking, but at least it’s thinking.

Moreover, Nikon hasn’t actually told those users what that means. For a D500 user, it means buying a somewhat bigger and more expensive D850. Why? Because you lose nothing—okay, you lose 1mp in the DX crop—while gaining things (e.g. full frame, kitchen sink features).

It’s interesting that Nikon doesn’t exactly see the D500 user clearly. A company that’s making the Coolpix 950/1000 isn’t seeing the “small but long lens and less expensive” proposition properly. At the consumer side, we have good Coolpix 950/1000 updates to the seminal 900. At the pro side we have the D6 update and the exotics, which were added to recently with the 120-300mm and 180-400mm. In the middle? Not much. The D500 is now four years old and the only D500-appropriate lenses Nikon has produced recently are the 300mm and 500mm PF. And this is just on the wildlife/sports side of things. The D500 user typically also wants a well-rounded camera, just smaller, lighter, cheaper, and with only a little less capability than the flagship. Still, even if we isolate just down to the wildlife/sports shooters, Nikon’s not doing enough to keep that crowd happy. And Canon? MIA for four years, and what little action you can point to appears to attempt forcing the 7D type of user down in capability (e.g. 90D).

What I want: The prosumer models to carry on, as before. Nikon did a decent job of this with the recent D780, but the Canon 5D and 7D, and the Nikon D500 and D850 all need the same attention.

At the bottom of the still-buying customers we have the casual shooter. I hesitate to call them consumer, because cameras are no longer a true consumer item (they’re no longer mass market).

The casual shooter already has an ILC. It’s sitting in a closet somewhere most of the year, and comes out only for special occasions or vacations. Over the years, it’s begun sitting in the closet longer and being used less, mostly because it isn’t convenient. This is the customer that smartphones have won over, but I hear complaints from this user about things their smartphone can’t do.

That’s the dynamic that’s important to this customer: convenient but competent. Smartphones are convenient but not always competent at some photographic tasks, while DSLRs (and mirrorless) are competent but not always convenient.

I’ve pontificated at this dilemma at length in the past, and I’ll again note I began doing so back in 2008, but the camera companies for the most part have never figured this out. The key elements are: smaller and lighter, coupled with ease of sharing images. A solid set of six or so appropriate lenses needs to follow the same guidelines: smaller and lighter, more convenient.

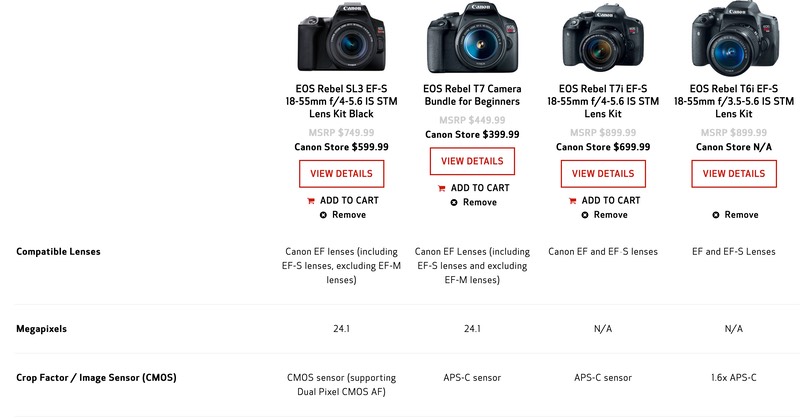

Canon got the smaller/lighter part right with the Rebel SL, but messed up most everything else. Because they tried to set the SL into an already crowded field of Rebels, they only confused the audience that might buy it. As I was writing this article, I decided to do a comparison on the Canon site between some Rebel models to refresh my memory. Look at this absolute marketing mess:

Megapixels are N/A on two of the cameras? What? Look at the other entries—this is just the top of an absolutely befuddling chart, by the way—there’s no consistency in what the crop factor is. Apparently there is no crop factor on the SL3 ;~). And did you notice that in the comparison, the SL3 photo looks bigger than the T7i? This isn’t a comparison at all, it’s a “can you guess what we’re hiding” game.

Remember what I wrote: convenience and competence. Convenience is important in purchasing, too. Canon has totally messed this up in recent years with APS-C DSLRs, and it’s no wonder that the sales of those are collapsing more dramatically than the overall market itself.

Nikon isn’t exactly hitting anything other than foul tips in the casual camera market, either. The D3xxx/D5xxx cameras are bigger than they need be, haven’t really been improved for years, and still miss a lot on the sharing and convenient side, despite SnapBridge being at least usable now.

What do I want? The smallest, lightest possible DSLR that has a solid set of basic features and controls, and shares images simply, conveniently, and with reliability. A truly appropriate lens set would be nice, too.

So who’s not buying cameras? The young, mostly. Whereas it used to be that college, marriage, or first baby tended to trigger a camera buying event, that’s not nearly as true today. I would argue that there’s absolutely no need to target this customer any more, both in product and in marketing. The best choice is to make sure the casual customers you already have are updating to the latest convenient and competent camera you make from time to time, and that should provide enough word-of-mouth to eventually reach new potential camera buyers (indeed, you can manage this through social media if you were making cameras that shared properly (Nikon almost gets this; SnapBridge has two auto-generated generic hashtag options, #Nikon and #SnapBridge, but doesn’t pick up the model number; e.g. #NikonD3500).

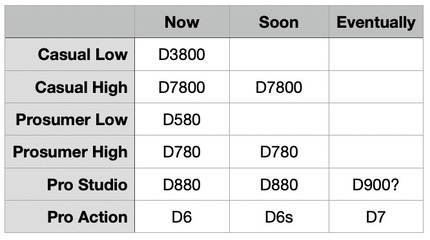

If those are the buying customers, how many cameras do you need to make? I’d say no more than six: two casual, two prosumer, two pro. Over time the DSLRs would drop to three, then when DSLRs finally hit their final phase out, one or none. Let me put the way I’d do it if I were running Nikon into a table:

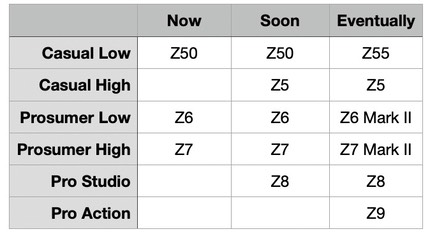

The opposite would happen in mirrorless:

Yes, that does tend to get rid of the D500 type camera, but Nikon already seems not so keen on that product, so I’m just reflecting their current predilections here.

My approach here adds up to 9 Nikon cameras short and medium term, 8 long term. I’d argue that this is the most the market can sustain and for which each could generate useful revenue and ROI. You could, therefore, try to eliminate some of these models and get down to 4 or 5 products. The problem with that is that you begin restricting one of your key groups down to just one option.

I’d argue that there are three groups you’re targeting (casual, prosumer/enthusiast, and pro), and you need options in each category. So at a minimum, we’re talking about 6 cameras. By contrast, Nikon currently has 9 DSRS and 3 mirrorless cameras, or double my minimum. I believe that’s trying to cut too fine a line on too few customers.

The traditional Japanese CES selling tactic was this: introduce a completely new technology with a high-priced single option, then follow up with cut down versions of it that went down deep into consumer pricing. Get the customer in a store door looking for that low-priced item, and up sell them. This is what generated at one point a series of Nikon cameras that went from US$400 to US$2000, in US$100 increments.

That’s also what drove Nikon from being a “system company” to being a “push consumer boxes company.” I’d argue that Nikon needs to return to selling a few products with a wide and full supporting system, not just trying to sell as many camera boxes as they can.

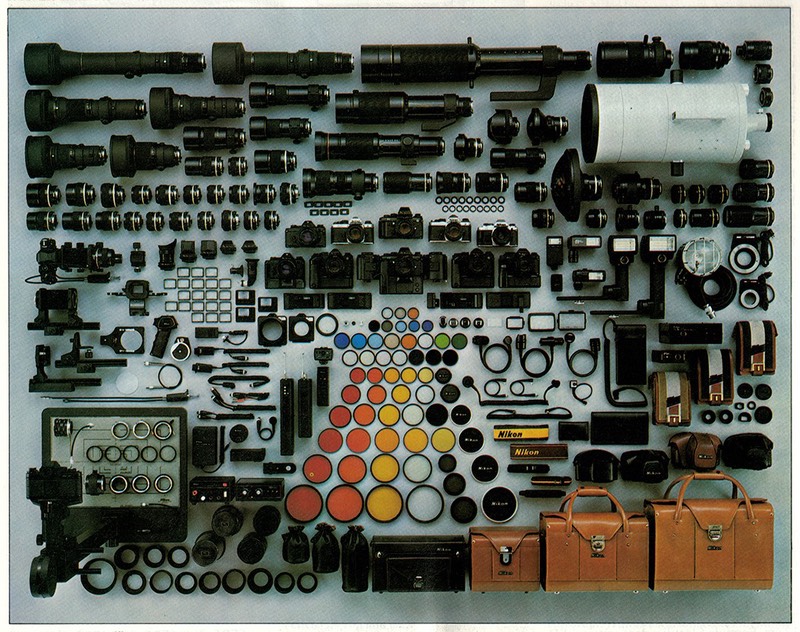

That’s Nikon’s “system” in 1982, back when ILC volume was far lower than it is today. You’ll note a number of things that Nikon no longer makes: bellows, ring flashes, extension tubes, and more. Nikon’s “system” today is basically just cameras and lenses. The flashes haven’t really been updated lately, the WR system isn’t usually in stock, recent bodies don’t get grip options, and we’re down to just a couple of remote choices. “Arca Swiss compatibility” is apparently a term Nikon heard of. One thing we do have more of today is free Nikon camera straps (included with the body).

The question you have to ask about a “system” is this: is there anything that’s photographically possible that you can’t do with the system? In 1982, no there wasn’t really a missing piece from Nikon’s system; they had pretty much every piece available. Here in 2020, yes, there are some things I can’t do with Nikon’s proprietary gear, and finding compatible gear to do it with my Nikon cameras either produces delays (new protocol not reverse engineered yet) or is still MIA (not possible yet). Oh, and remember the current cameras are also video cameras, which introduces a whole bunch of other “system” things Nikon doesn’t make, or makes poor examples of (I’m looking at you, ME-1).

So, as sort of a final comment, I have this: if you don’t make it, enable it. There’s a lot of things Nikon doesn’t make now, and they do absolutely nothing to enable it from others. The people who are still buying DSLRs (or even mirrorless) want full system capabilities, not limited ones.